Esther Myers has been practising yoga for over 30 years, including 10 years with Vanda Scaravelli who was and continues to be her primary inspiration. She is the author of Yoga and You; Hands-on Assists: A Guide for Yoga Teachers, co-author of The Ground, the Breath and the Spine. She has produced two videos: Vanda Scaravelli: On Yoga and Gentle Yoga for Breast Cancer Survivors. Esther Myers Yoga Studio opened in Toronto in 1979.

FOYT Space: The question of practice seems to be a good place to start. What are your thoughts about personal practice for yoga teachers specifically? And with all the travelling, writing and teaching you do, are you able to maintain a practice? What does you practice consist of? What is you experience of a personal practice and how has it evolved over the years, both theoretically and in reality?

Esther Myers: I think personal practice is essential if you are teaching. I don’t really see how you can teach without it. I think it’s a resource. It’s a way of coming back into your own centre and entering into your own process. You need that return back to yourself, which is different than doing poses with a class. Certainly people vary in how much of a class they do with students, but I don’t think that’s a substitute for personal practice. I think you really have to have your own practice. What practice is going to consist of, is going to vary tremendously from person to person, because of age, physical abilities, needs, stamina and style. That a teacher needs to be practicing, I would say absolutely.

My practice … I started off young, and I started off in lyengar yoga, and I could do the poses easily. I loved them. I didn’t have any trouble learning them. While the method itself is very challenging, there was also something very natural about it for me.

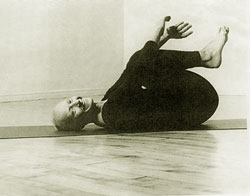

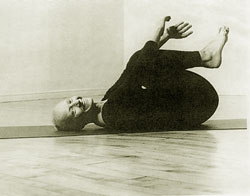

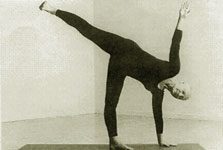

Two things have changed it. In 1984, I started studying with Vanda Scaravelli. Vanda wrote Awakening the Spine, and she was originally a student of lyengar’s, one of his very first students. Then she developed her own style, which incorporates the breath a lot more. It’s much more fluid. It’s much more feminine. It brings what she called “the wave”, or an undulating organic quality into the postures, in a way that I think is unique. That was a huge, huge change in my experience of yoga.

She taught one to one. She was a very hands-on teacher. There was a dynamic quality to her teaching, and at the same time, as her student, I really had to surrender to it. That was a new and different experience. So that was a major change, and it was a major change philosophically, in the sense that her focus was on unwinding, undoing, doing less, letting go.

The other big, big change in my practice happened ten years later, in 1994 when I had a mastectomy. The night before the surgery I did Wheel in the hospital, at three in the morning, when I couldn’t sleep. The next day I couldn’t move my arm. That meant learning to rebuild my practice from scratch, and I’d never done that. It wasn’t like I started off really stiff and had to struggle with the poses. After the operation I had this very strong self-image of, I can do all these poses. I really pushed myself to get back to where I’d been, and then I’d injure myself … It was a real struggle, both physically and psychologically.

I recover very slowly from surgery. I had less much energy, and I also had to learn to respect that. Vanda said to me, “relax”, “don’t push”, “take it easy”, “rest”. A traditional Chinese doctor wanted me walking briskly for an hour to an hour and a half a day. I’d say, “I’m tired”, “my arm hurts”, “my knee hurts”. He said, “Just do it”. Like a Nike ad, “Just Do It”. They were both right. The walking helped me rebuild my energy when I could not move very much in terms of yoga, and I needed a lot of rest. The issue has been balancing those two.

I had a hysterectomy in 1999, and I realized then that I knew how to respect my body, to go from where I was, to rebuild through that. That’s been a huge change. Again, I had over a year of feeling that I needed a lot of rest.

Two years ago, I was diagnosed with a spread of the breast cancer into my abdomen. Not into the organs, but into the space. I was able to carry on functioning with it. My oncologist wanted me to have chemo very much. He was prepared to watch and-wait, but he said, “If you start to feel unwell then we have to act very quickly”. That happened last October. I started to feel drained, depleted, like this thing was really eating me alive. At that point, I made the decision to start chemo, and also went public with the condition.

The chemo’s been a surprise. I thought it would be hell, and it hasn’t been. I think it’s a combination of the conventional drugs, the complementary drugs if you want to call them that, and the fact that my chemo has actually reduced the tumour. So I’m feeling hugely better now than I was six months ago. My vision of chemo was that it was going to be six months of hell, and then maybe I’d feel better as a result, and it hasn’t been like that. My main symptom is fatigue. So I’m back in a cycle where I have to rest a lot, and I have to adapt my practice to my energy. Sometimes my practice feels fabulous. I feel doing Wheel now has been won back three times. When I started, I could just do Wheel. That’s a huge shift.

In Yoga and You, you wrote that before diagnosis, you had been absolutely certain you were cancer free.

My mother died of cancer, but it wasn’t going to happen to me. “I have it together”. I’m fine”. “I’m living this healthy life”. The diagnosis was a real shock. There was no call for me to have chemo at that time. A lot of people assume that I rejected it then, but I didn’t.

How did you come into teacher training? What draws and inspires you to teach aspiring Yoga teachers? The teacher training offered through Esther Myers Yoga Studio is a two-year process. What are your thoughts and views on teacher training certifications?

My original training was in Iyengar yoga. I grew up in Toronto. In 1969, I moved to London, England for seven years, where I started yoga. At the time, there were two main styles of yoga in England: lyengar, and another one called the British Wheel of Yoga, which was more like what people now call hatha. For me, lyengar yoga was just yoga as I knew it. I moved back here, and people had heard of lyengar yoga, but nobody was really teaching it. It was just beginning here.

There were a few people in the States teaching it, me, and Bruce and Maureen Carruthers on the west coast, but it was really just germinating.

I started giving classes at Yoga Centre Toronto, which was teaching classical hatha yoga. Nobody had ever heard of alignment, so I had a whole body of information that was new.

Philosophically, people were working from a place of don’t push, if it hurts don’t do it, whereas the lyengar system really challenges you to go to the edge, and go through it. Each system has its benefits and its drawbacks. The benefit of not pushing it is exactly that, you don’t strain, you don’t force, and so on; the drawback is that your practice can get very stagnant. The benefit of pushing it is that there is the dynamic quality; the drawback is that you can push too far. There were a number of people who found this dynamic – to go to the edge, and take it further – quality, really exciting. It gave their practice a whole new dimension, a new edge, and a new challenge.

I was instantly teaching teachers, which was terrifying for me. I’d just finished my training, got on a boat, came back, and all of a sudden, four months later, I’m teaching yoga teachers. For me, it was a very anxiety-provoking situation.

I got involved in training teachers when some of my own students got interested in teaching lyengar yoga. Some of them wanted to learn to teach yoga. Some of them were already teaching yoga, but wanted training in lyengar yoga. My training was entirely apprenticeship. I just hung out in yoga classes, in the UK, a lot. lyengar named about twelve people, senior teachers, and they were qualified to accredit other people. You needed the approval of three of them to get a certificate. There was no course as such. In that sense, it was much more traditional. You hung out with a teacher until they said you could go on. That became the basis of my training. When I started training teachers I asked people to be in my classes, as a student, and observe. We had very informal discussions and seminars. We found that it took a year and a half or two years for people to integrate what I was trying to teach.

My course is two years because it still feels to me like that’s the time it takes for people to integrate both the information that you need to learn, and the internal process. We still require an apprenticeship. We also ask people to teach a class a week in the second year of the training. So you’re getting your initial experience as a teacher at a time when you can still come back to us and ask questions. There’s time to take the information you’ve learned, integrate it, and put it into practice, while you’re still in a context of support and supervision.

What is the requisite background for aspiring yoga teachers to come into your program?

They have to have been studying yoga for two years, and then they have to have a personal practice. In other words, they’ve got a fundamental baseline established, and then a personal practice. For some people, getting their personal practice established is one of the big challenges of the program. It’s not that they have to have had a personal practice for two years, but they do have to develop it. And these days that can be a huge issue. There are people working full time, with kids, and they say that the time for their personal practice tends to be between 11 pm and midnight. It’s a huge challenge for a lot of people.

You came into yoga through asana? When did you become aware of the bigger picture, the seven remaining limbs? How has awareness of the eight limbs affected your life, your person, and your world? How did it come to you?

Where the philosophy comes into it, is a funny story. When the Yoga Alliance was being formed in the States, I was involved in a panel discussion at Kripalu about the whole question of certification. The woman beside me was talking about how she went over to London, and there were all these people that knew about kneecaps, but they’d never heard of the yamas and the niyamas. I was sitting there thinking, I was one of those people.

I started teaching just around the time that FOYT was being established. The thinking was way ahead of its time. Some teachers felt if yoga teaching did get established, or regulated in some way, that there should be some kind of organization involved.

The founders sent around a questionnaire to get people’s feedback. One of the questions on the questionnaire was “Do you think a yoga teacher should know something about yoga philosophy?”

I was in a really funny position because I didn’t, and I was teaching all these teachers. At the same time putting no on paper seemed a little odd.

So when I started training teachers, I thought we really ought to do some yoga philosophy. We’d take these books of the Yoga Sutras that were 200 pages thick, really dense, really obscure, and try to fumble through them. It didn’t work. There are much more accessible translations available now, that are very readable and concise. It’s much easier to access the teachings now, than you could back then.

I’ve also had a lot of personal issues around the philosophy in the sense that, even after the better translations came out, I had trouble connecting with the texts. It took me a long time to formulate why. The first clue was when I was reading one of the Upanishads that talked about the student going to death, and saying, “I want you to be my teacher”, and death saying, “No, no, no, go find another teacher”. This is very classical. And the student said, “I want to study from you, I want to know what’s beyond death, what’s real, eternal”, etcetera.

When I was diagnosed with breast cancer I thought I had two years to live. There was no medical basis for that thought. It was my own fear. My question was, if I have two years to live, what do I want to do with those two years? It wasn’t, I want to find out what’s real and eternal. I realized that part of the reason I wasn’t relating to the text is that it wasn’t describing what I felt when I faced death. So I started to look at the texts asking, what part of this does relate to me, what does not. For instance, the Yoga Sutras talks about illnesses as an obstacle. Illness for me has been a driving motivation. It’s really pushed me in profound ways. So I don’t see illness as an obstacle in quite the way I think the text is talking about it. As I became clearer about that, that there are some ways that these works speak to me, and other ways that, they don’t, I started to see a different relationship to the text.

Vanda also influenced my thinking. She said, “I studied with lyengar and developed my own way, you should take my teachings and develop your own way”, and when I asked her how she developed her own way, she said, “I just trusted my body”. Now that was not something that came naturally to me; it was something I had to learn. What I’m seeing now in the yoga world, is people – and this includes teachers – looking to outside authority to tell them how to do the poses. It works if you stay within one system, and you absolutely believe in that system. However, the profusion of information, books, tapes, conferences can become very confusing. The question that I hear a lot is, “Now I don’t know which way is right”. The question that doesn’t come up is, “How do I find out which way of doing this is most effective for me?”. I want to help people to choose which way they want to do a pose at any given time, with the understanding that each particular way has its own unique effect. I’m trying to train teachers to make the practice their own.

We can take that same approach to the texts. For example, rather than saying I follow the yamas and niyamas, I ask, what are the values underlying my teaching, what are the values that I bring to my practice.

The classical texts are a distillation of wisdom, but they are also coming out of a particular culture, and a particular time. It’s mainly women doing yoga now. How does that change our perspective? That question hasn’t really been addressed in the yoga community. In that sense, the yoga community, I think, is very conservative. There hasn’t been a feminist revolution within the yoga community. Many of the senior teachers are men, and the philosophical viewpoint is fundamentally male. I feel a real call to start to address these issues. Here we are, western women, doing yoga in a very different framework than the traditional teacher/student relationship. How do we articulate the meaning of this practice for us? How is that congruent, or not congruent with a classical text? I think those are important questions, and I think they’re not being asked very much.

The issue of there’s more to this than just the poses is actually intellectual. The fundamental value I bring to this is the need for authenticity; that has been central in my own personal process.

To give you one example, the night before I started chemo, I was completely freaked. I thought it was going to be horrible. I hadn’t wanted to do it. I mean, I fought chemo like crazy, and I wasn’t feeling well. I called a friend of mine, and he said, “Authenticity above all should be all”: Which is actually what I believe. So, you don’t have to pretend you like this, now’s the time to do it, but you don’t have to think it’s positive, or anything like that because you never did. The fact that it’s turned out to be, is another story. But just in that moment, what do I truly feel, what do I truly believe. That has been underlying my whole process since the beginning. So authenticity is a very, very strong value for me, and that’s become clearer as I’ve gone along, but it’s always been there. I think there’s this dialogue or tension — tension in the best sense of the word – between the text which says these are the values, and being true to oneself. There are values implicit in any style you are teaching. No pain, no gain, is one extreme. If it hurts, don’t do it, is the other extreme. Stay on the edge, and still keep a steady breath, would be another value. There are values underlying your teaching, no matter where you place yourself in that spectrum. Can you make those values conscious, and in doing so be clear about what they are? Then they are yours, and people who share them will be drawn to you. Right?

Teaching teachers to have their own method of teaching? Doesn’t that come from time and experience? Isn’t it difficult enough to teach teachers what and how to teach?

It does come from experience. It is difficult to teach, but I think that there are two pieces to that. One is the fundamental understanding of anatomy, so that I know what the body can safely do, and what it can’t safely do. For instance, hyper-extending the knees is a stress on the joints. There is no pose where hyper-extended knees is correct because you’re actually damaging the joint in the process. So we can look, and say that the pose is wrong if you’re hyper-extending your knees. But if we ask, what is the correct position of the leg in pigeon pose, then we look at the hip joint, and see there are lots of different positions your leg could be in that would not be anatomically incorrect. Within different styles there might be different ways that the pose is done. You can then choose between them, based on your hips, your interest, and also the question of do I want to take this pose to the edge, or do I want to stay short of that, and so on.

The other issue is teaching people to listen to, and trust their bodies. I was teaching a workshop at Kripalu. One of the people said, “My lower back hurts in cobra”. The person beside her said, “Make sure you keep your pubic bone on the floor”, and the first woman said, “No, that makes it worse”. Here you have two people, side by side, one’s back is better if she keeps the pubic bone on the floor, and one of whose back is worse. You can’t say, this is the right way to do cobra. The question is, what’s the right way for you to do cobra. It means actually finding out what works for you, and for any particular student. We can start to educate people to respect what their own body tells them. I’ve had people say to me, “When I do a pose this way it always hurts”, and I say, “Well, change the way you do it”, and they say “But I was taught that this is the right way to do it”. It doesn’t matter what I was taught. If doing a pose this way hurts your back, then change it.

There’s a lot of empowerment of the student that needs to come in. Somebody in one of my workshops at Kripalu said that the Dalai Lama published something called, Thirteen Principles of Wise Living. She brought it out, and said here’s the one for you. It was learning the rules so that you can break them properly. That’s what I’m talking about. I think you need to be educated in anatomy, you need to be educated in alignment, and at the same time, attentive to, and profoundly respectful of your own body, and also aware of where your body needs to be challenged. I think you can teach people that, but it’s not easy. It’s a much more complex process than: “This is how to do triangle pose. Your job is to conform to what I’m telling you”.

And what are your thoughts on simple basic hatha yoga, incorporating breath and asana? What about the concept less is more? Ultimately, is it all about becoming still and quiet? And what exactly is it about deep stillness and quiet? Is it yet another placebo? Is it just another venue for the mind to comfort itself? Are we kidding ourselves?

Vanda Scaravelli placed a huge emphasis on breath, and again, that was a real shift for me. She brought the breath into the poses to facilitate movement, which she called the wave. It had a very, very dynamic quality to it, and for her, personally, the breathing – and this is the opposite to the traditional eight limbs – supported the asana practice rather than the other way around. As many other people do, I started with the poses. I had no sense at all of anything other than this is the pose. I loved them, and I think that the poses can speak for themselves. If you see a dancer that is inspiring, you don’t say are they practicing the Ten Commandments. The medium can speak for itself, from itself, and I feel that way about the postures. I don’t think that you necessarily need to go outside them to find something else, unless you’re interested in doing so. But if we actually come from within the posture, then what does that speak of, or express, or access.

Certainly for me personally, sitting still hasn’t come at all naturally, and I finally gave up. I thought, forget it. About two years ago, I just gave myself permission to move every time I felt like it, to bend over, or stretch, or fidget, or whatever. It was wonderful. Now when I sit still, it’s because I’m actually still. In terms of my own practice, if I don’t feel like sitting still, I don’t. There are other ways to practise.

How has living with cancer affected your life, your person, your teaching, your writing, and the. giving of yourself in the yoga community?

It affected me hugely. The first thing was, I told my classes that I was going in for a biopsy. I have a very public side. I have a very private side. Telling my classes that I was going in for the biopsy, and then telling them that I was diagnosed, was a huge shift in bringing what would have been private, public. It felt very vulnerable, and I felt very exposed. What came back was this wave of unbelievable support. I mean, it was amazing, and it went on for months. Marion Woodman has talked about the same thing. People would say, “I haven’t called you, but I’ve been thinking about you, and am sending you healing energy”, and I felt it. I just felt like I was surrounded by light.

What made you open up?

I don’t know. Certainly I would have had to tell people once I was going in for a mastectomy, but what motivated me to tell them before, I don’t know, but it was certainly a shift. On the whole, I’ve been public about the experience, although with this abdominal thing I was quiet about it for about a year and a half In other words, I didn’t go public with it until I had to, and in the last couple of months that became a stress.

Physically?

No, emotionally. Pretending that I’m okay when I’m not, when I’m really not doing very well. I was exposing myself as something other than strong. “I’ve just been diagnosed with cancer” is not a strong place. It really meant exposing a kind of vulnerability I’d never done before. That has continued, and it’s affected my writing a lot.

Two people, from completely different parts of my life, have said to me, “What was your practice like after your mastectomy?” and I said, “It was really lousy”, and they said, “I bet if you wrote from that place, people would really relate to it”. So I wrote an article that came out in Yoga Journal in December 1998, on my experience of breast cancer, and people did relate to it. I was scared, and I was frightened. I was looking at the cover of my book in tears because I couldn’t do that pose anymore. That has resonated very strongly for people. So the question is, how can I continue to write from that place. I’m in the process now of writing another book which explores those kinds of questions much more fully. The writing is easier now, but the initial resistance was, how dare you put this on paper.

To yourself?

Yes, to myself, and with the thought that this will be public. I was at the Yoga and Buddhism conference at Kripalu last December, and a number of people there, mainly the Buddhist teachers, were remarkably open about their own experience. It was a real model for: “You can be honest”. You can be honest – in that case – in front of 250 people. What I’m finding now is that I don’t have the resistance to the writing itself. The basic process is to get everything on paper, and then you can decide what you want to make public. I don’t have the struggle getting it down on paper that I used to.

I just did a little article for a book that Stephen Cope is editing. In it I said that my practice has been such a struggle. It’s often hard to get to my practice because other times I can forget I have cancer, and when I get onto a yoga mat, I can’t. I had this twinge of, as a well-known yoga teacher, can you admit to that, on paper, in black and white? Another shift that came through cancer was that it made me honour my own body, which was a huge shift. Another thing I think comes through strongly, although it’s hard to define, is that because I’ve been public about this, people know what I’ve been through. I think that creates an authenticity in my teaching that people feel, even if I’m not teaching any differently than I used to.

Do you have any religious affiliations? What are your thoughts on the soul?

I’m Jewish by birth and culture. I’m not particularly practicing. Somebody, several years ago, said to me that there’s something in me that resonates Jewish, and I think that’s still true.

Interviewed by Deborah Mitchell

Photographs by Cylla von Tiedemann

Published in FOYTSpace, June 2003